Lyttle Lytton Plus GPT2—Continuing on atrocious beginnings to novels

Little Lytton

The annual Bulwer‐Lytton Fiction Contest challenges entrants to pen the world’s most atrocious first line to a novel. Winners (and runners‐up and honorable mentions) are generally very long. The inspiration for the contest is the opening sentence of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Paul Clifford:

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Brevity is the soul of wit, and this goes on and on and on. Adam Cadre’s Lyttle Lytton Contest proposes an alternative contest, inspired by an alternative:

Jennifer stood there, quietly ovulating.

The non‐action of “stood”, the vagueness of “there”, the involuntary process of ovulation treated as an activity, the inappropriateness of measuring the volume of that non‐activity, the uncomfortably gynecological detail of mentioning it at all—all combine to make a cringeworthy sentence. And since it’s only five words long, its impact is instant; you don’t have readers slogging through clause after clause after clause.

I decided to use the GPT-2 large model, in the 🤗 Write With Transformer interactive environment, and extrapolate the first paragraphs from many of these atrocious sentences.

2000, version 1

Jenny stood there, quietly ovulating. She had her arms spread out in front of her. "And I would like it if your first child would be a girl," Jenny told the crowd, her eyes wide and her cheeks still flushed.

We see her in a beatific pose with arms embracing her audience, we encounter her in medias res as she is preaching to an audience (of expectant first-time parents?), we observe the conflict between the non-action of stood and the vagueness of there with the rush of blood to her cheeks and the dilation of her pupils, we note the delicacy of the subjunctive mood and the inappropriate bluntness and personal nature of the wish.

This takes the punchy confusion and overpersonal cringe of the initial five-word sentence, and expands in many dimensions. The first sentence provokes an unease as to where to the story is going, and the exposition amplifies all of those emotions as it continues.

2000, Version 2

Jennifer stood there, quietly ovulating. She knew that he was probably in the room, but she didn't have to know it. "I'm not doing that to you," he warned. "I just wanted to be sure," she said. He looked down at her and smiled, but he didn't say anything.

This is a quintet of banal and profound discomfort.

The non-place-ness of there continues with in the room. The involuntary process of knowing treated as an activity, and the odds of her knowing this, and the implication that her mind is being directed, mirrors the introspection of her involuntary processes from the first sentence. We get the first intimations of conflict, as she receives a warning from an unnamed “him”. The dialog, preceded by knowing his probable presence, implies a sort of summoning that Jennifer does, to assuage her own uncertainties. The position of him looking down at her and smiling silently is vague enough to imply that he is non-corporeal, that he is a shade of someone Jennifer had known, present in spirit in the room, and she is hallucinating the entire dialogue, brought about by some (other?) entity causing her to know his probable presence.

Version 1 is almost preaching to a crowd, Version 2 is almost talking to a ghost.

2003

For centuries, man had watched the clouds; now, they were watching him. And as the clouds grew larger and larger, it became clear that this was nothing more than an experiment to see if man would survive , as they had before.

The ominous meteorological foreboding turns into a cyclical drama, where human extinction could be the experimental result of growing clouds surveilling humans. Perhaps a heroic triumph over cloud seeding is in the middle of this saga.

2004

This is the story of your mom’s life. It's a story of love and betrayal and love and betrayal. It's also a story of the rise of a woman that you have come to love and adore. It's also a story of the death of her love.

The Lyttle Lytton contest describes the beginning thus:

“This pretty much sums up what this contest is all about: it’s somehow ruder than the overtly rude ones, funnier than the ones that are trying to be funny, and actually sounds like the beginning of a novel and not just a line from the middle of one. And it’s eight words long.”

The love and betrayal is duplicated twice, which seemed initially repetitive but uselessly vague, and the third sentence’s incestuous implications make this clear: this is the story of Oedipus Rex’s mother Jocasta! The first love and betrayal is Jocasta’s maternal love for Oedipus, betraying her husband’s filicidal wishes. The second love and betrayal is Jocasta’s new marriage to Oedipus, the happiness of which is betrayed by common ignorance of his birth family to all except Tiresias. The death of her love unwinds both loves, as she discovers who her second husband is.

2009. Intermezzo, dreary pablum

From the contest:

For instance, I just went to the suspiciously heterosexual Amazon bestseller list and pulled up the top book, which was something called Liberty and Tyranny by one Mark Levin. It begins:

There is simply no scientific or mathematical formula that defines conservatism.

See, that would be a winning entry in this year’s contest! It raises a number of questions: who exactly does the author think he’s disabusing of the notion that a political belief system can be rendered as a “scientific or mathematical formula”? What distinction does he believe he’s drawing between scientific formulas and mathematical ones? How deep into this imaginary argument is he that he thinks he needs to add the word “simply”? Most importantly, it doesn’t make me want to learn the answers to any of these questions. The first sentence convinces me that the author isn’t going anywhere with this that I have any interest in following.

We can use spinnerets powered by GPT-2 to excrete ever more:

There is simply no scientific or mathematical formula that defines conservatism. To the contrary, conservatism can be defined as a set of attitudes and behaviors that a conservative holds with respect to a wide variety of issues, including but not limited to those relating to public health, the environment, national defense, foreign policy, immigration, and social issues. To the extent that any given issue might be considered a conservative issue , one would have to consider those issues in the same way one would consider an issue on a left-of-center or center-of -left spectrum.

2010

“I shouldn’t be saying this, but I think I’ll love you always, baby, always,” Adam cried into the email. "I really love you." She replied, "We know", and then sent the email to her boss. The message is not part of the evidence the Crown's lawyer presented during the trial, and it is unclear whether it was ever intended for publication. Story continues below after advertisement

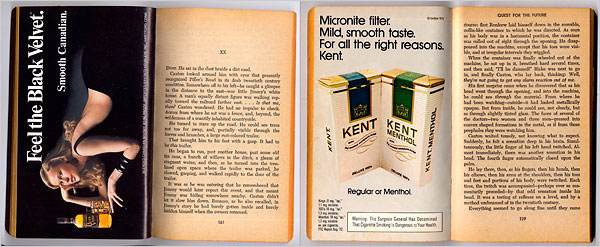

There is, indeed, “so much wrongness packed into those four little words” of “cried into the email”. Forwarding love notes to the boss implies a lengthy HR procedural, and the intimations of trial evidence implies a lengthy detour through discovery and cross-examination. The “story continues below advertisement” was a gem to behold, a throwback to when Dr Spock’s “Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care” had ads for Q-Tips and A E Van Vogt’s “Quest for the Future” had liquor and tobacco ads:

2012

She had the kind of face that made you want to say hey, look at your face. But, it was all so natural. So, you're like, I guess I have a problem. I'm pretty normal-like.

This 2012 runner-up takes the initial comedic prompt, continues in the vein of flat-affect underdescription, and veers towards the Eye of the Beholder Twilight Zone episode.

(from Attractions Magazine)

2016

It all started when my topaz eyes looked up into his soft emerald ones. He looked away, but I couldn't help but notice his emerald eyes staring back. He turned his head just enough to meet my gaze. I was in the zone now.

As those who have read previous Lyttle Lytton pages know — because I say it almost every year — when I’m going through the entries, I ask myself, “Does this sound like the beginning of a novel? Is it hilariously bad?” If the answer is yes on both counts, the entry will probably show up in the list of winners. But the first-place winner has to clear another bar: “Is this plausibly the beginning of a novel?” So, here we have the entry above. Do writers ever compare eyes to gemstones? Of course — so much so that it’s a cliché, though a forgivable one. Do writers ever write about a character’s “soft eyes”? Sure. So it is absolutely plausible that someone would blithely dash off the phrase “soft emerald” without taking a moment to register that, whoops, no, that really doesn’t work at all, does it? Verdict: winner. (And now I have to assume that an AI constructing the ultimate Lyttle Lytton sentence based on past results would write about “gazing into the chaos emeralds of his eyes”.)

When his head turns to “meet [their] gaze”, as he is looking away, is he craning his neck still looking away? The mesmerizingly inept pile of clichés continues apace.

Most completions of this beginning:

It all started when my topaz eyes gazed into the chaos emeralds of his eyes

have a single period; the sentence is purely magical awfulness and stands by itself.

Try some yourself and publish the best ones!

Part of what is fascinating to me is how much is still dependent on human curation and human taste: note how different the 2000 v1 is from v2, preaching to a crowd versus talking to a ghost. What would be interesting would be to be able to specify (in some way, in some potentially different model) what aspects, which Adam Cadre in the Lyttle Lytton contest notes, are so tantalizingly repulsive that they should be maintained throughout, versus relying so heavily on manually pruning the search space of continuations.